The whole SAIS framework is created to make it relatively easy to make your own games and not be limited to just snake.

SAIS is primarily written in Rust and when I crated it I explored various technologies and overall learnt a lot. These inlcude:

- Tokenisation + Recursive Descent Parsers

- Code Generation

- Executing untrusted code

- SQL Databases and ORMs

- Rust Async Code

- The HTTP Protocol

- Server-Sent Events

Some screenshots of SAIS

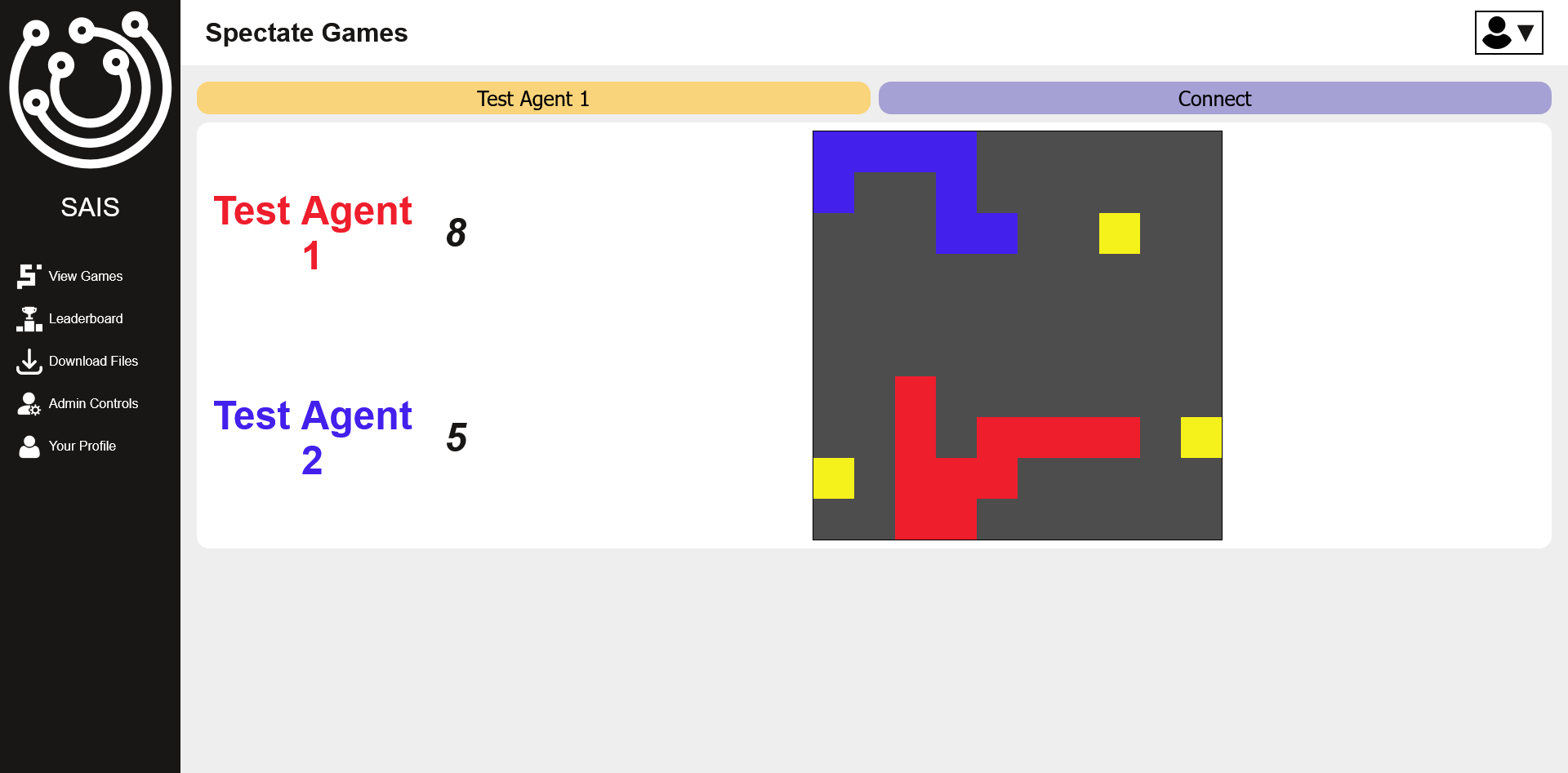

Spectating Games

After writing and submitting your agent, you can watch it play live against other agents on the SAIS website. Here you can see a screenshot from a game between "Test Agent 1" and "Test Agent 2". Test Agent 1 has a score of 8 while Test Agent 2 has a score of 6.

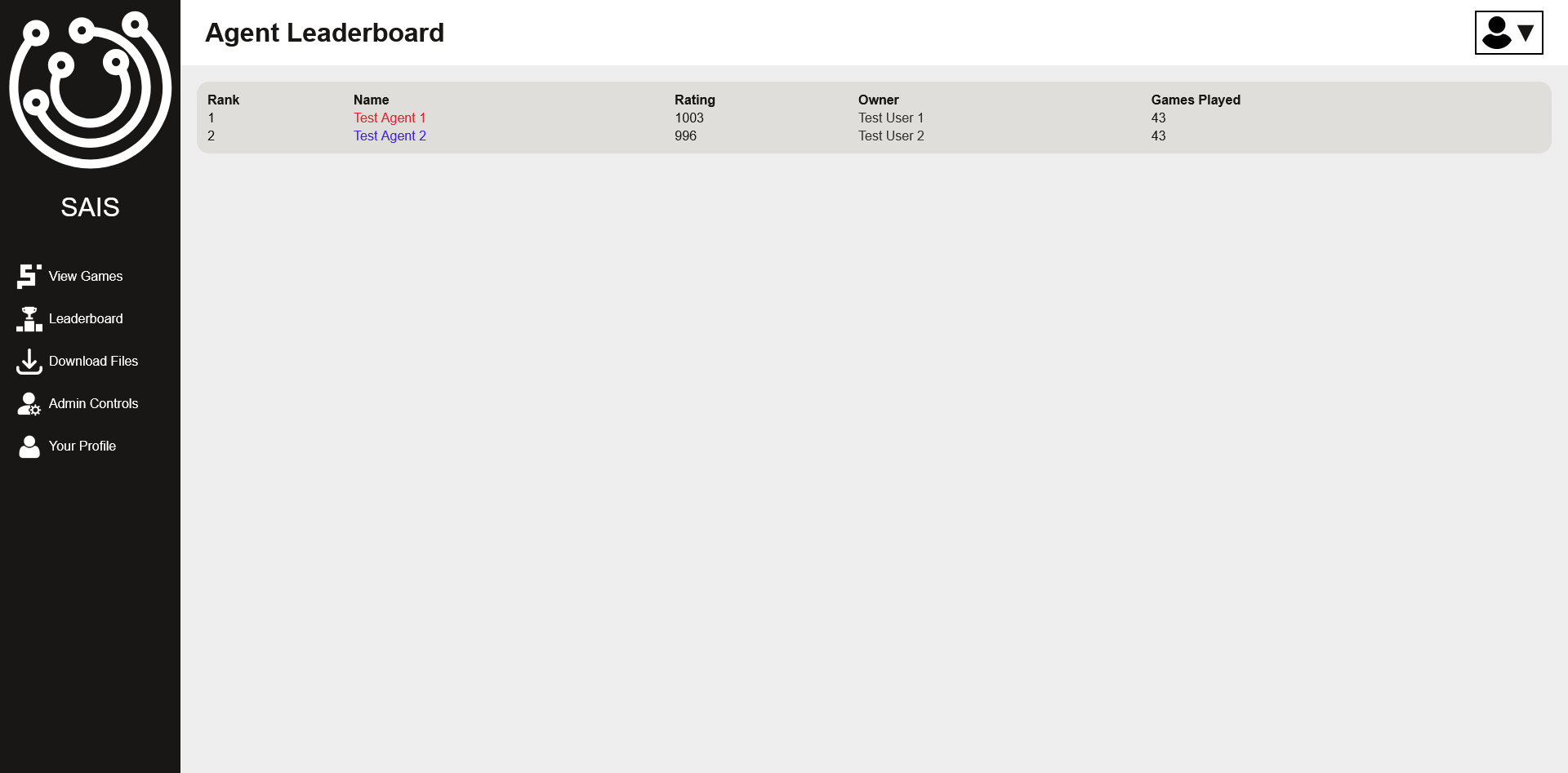

The Leaderboard

Every agent you submit is assigned a rating. After every game it plays, its rating is updated based on the results of the game. This system is inspired by the Elo rating system. Then, you can view the ranking of all the agents and (most importantly!) see who is first.

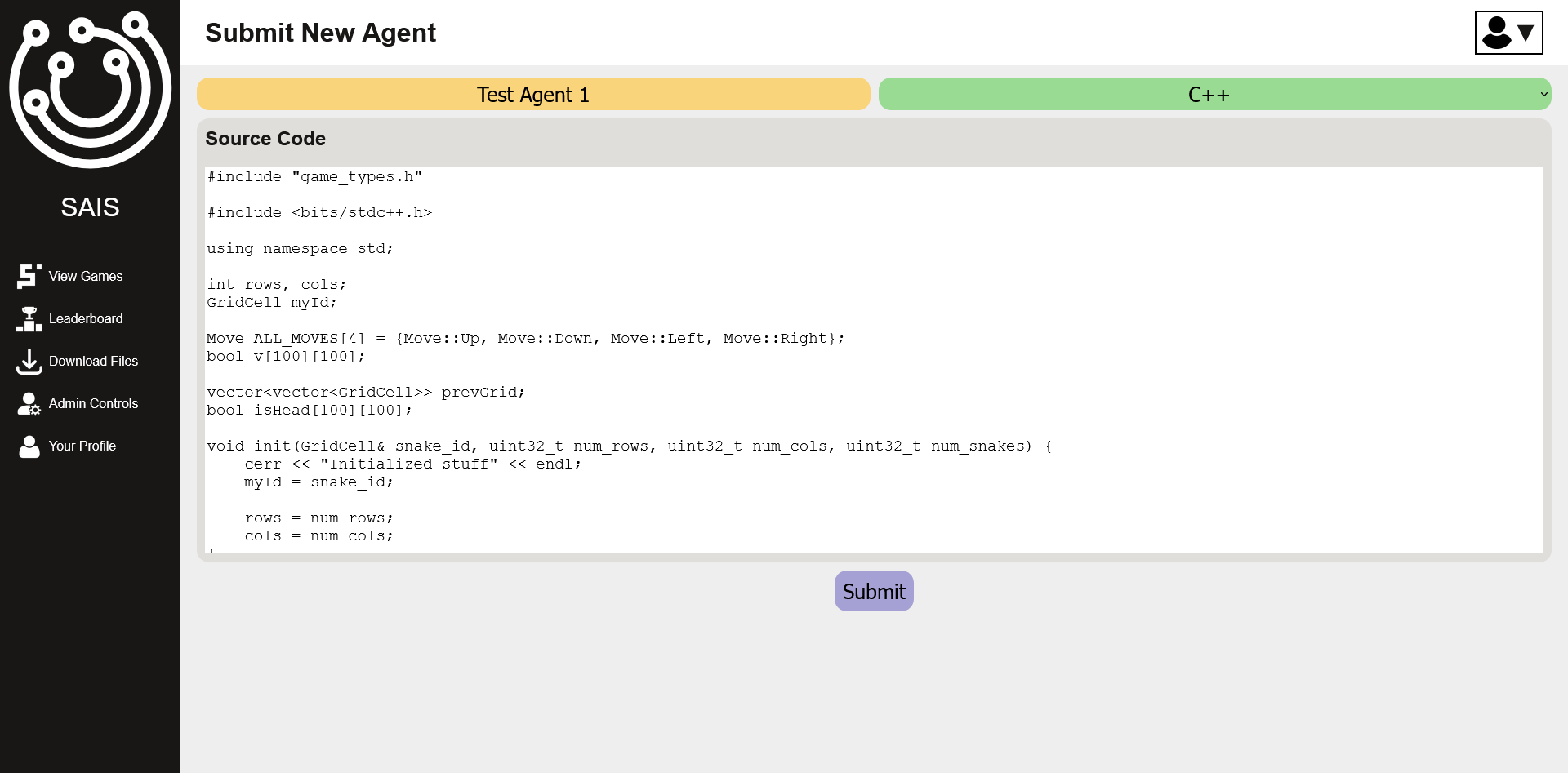

Submitting an Agent

Here is the page where you actually submit your code. Currently the two supported languages are Python and C++. Then, you just name your agent and you're on your way! This code here is taken from one of my best snake-playing agents. For a more basic example of what an agent looks like, you can see the default agent below.

Recursive Descent Parsers? Why?

As stated previously one goal of this project was to make it as easy as possible to implement your own games (so this project isn't restricted to just playing snake). The first step in creating a game is defining the interface the agents will need to implement. This is done in a .game file which looks like below:type GridCell = i32;

type Pos = struct {

row: u32,

col: u32

};

type Move = enum {

Up, Down, Left, Right

};

function init = (snake_id: GridCell, num_rows: u32, num_cols: u32, num_snakes: u32);

function get_move = (grid: [[GridCell]], head: Pos) -> Move;

The file above defines three types. A GridCell type which is actually just an integer in disguise. A Pos type

with two member fields row and col, representing a pair of integer coordinates. And finally an enum type

describing the possible moves a snake can do.

It also defines two functions that the agent must implement. An init function which presumably would be called at the start of a game, providing information like the size of the grid and the number of snakes playing ahead of time. Then there is the get_move function which would be called every game tick, giving the agent the state of the grid, and the position of its head and asking it to select a move to perform.

The structure of this file is very heavily inspired by the rust type system and is quite simple. Because of its simplicity, the entire tokenizer and parser for this file format is only about 400 lines of code.

Code Generation

The information stored in these files is used to automatically generate a lot of code, in various different languages, designed to speed up the process of implementing these games.Client-Side Code

The only generated code any person "competing" on SAIS would see are the skeletons for implementing an agent. Firstly, all the type definitions are translated into suitable types in the required language. Currently, the only two supported languages are Python and C++. The C++ type definition for the file above would like below.#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <array>

#include <stdint.h>

typedef int32_t GridCell;

struct Pos {

uint32_t row;

uint32_t col;

};

enum class Move : uint8_t {

Up,

Down,

Left,

Right,

};#include "game_types.h"

void init(GridCell& snake_id, uint32_t num_rows, uint32_t num_cols, uint32_t num_snakes) {

//Implement logic here...

}

Move get_move(std::vector<std::vector<GridCell>>& grid, Pos& head) {

//Implement logic here...

return Move::Up;

}Agent "Interactor"

The server cannot directly interact with a program in the format above. All the agents are run as separate processes to the server so there needs to be a way for the server and a running agent to communicate. This is where the "interactor" comes in. The interactor for C++ would look something like below (the version below is shortened quite a bit). It deserializes commands from the server and then serializes the results to send them back to the server. In the case of C++, the agent would be compiled against the interactor code.#include "game.h"

#include "interact_lib.hpp"

/* Some (de)serialization helper methods defined here */

int main(){

std::cerr << "Starting Interactor!" << std::endl;

while(true) {

uint8_t func_id;

readData<uint8_t>(func_id);

if (func_id == 0) { // init

std::cerr << "Calling function init" << std::endl;

GridCell param_snake_id;

read_GridCell(param_snake_id);

uint32_t param_num_rows;

readData<uint32_t>(param_num_rows);

uint32_t param_num_cols;

readData<uint32_t>(param_num_cols);

uint32_t param_num_snakes;

readData<uint32_t>(param_num_snakes);

init(param_snake_id, param_num_rows, param_num_cols, param_num_snakes);

} else if (func_id == 1) { // get_move

std::cerr << "Calling function get_move" << std::endl;

std::vector<std::vector<GridCell>> param_grid;

uint32_t size_0;

readData<uint32_t>(size_0);

param_grid.resize(size_0);

for (int i = 0; i < size_0; i++) {

std::vector<GridCell>& baseAddr_0 = param_grid[i];

uint32_t size_1;

readData<uint32_t>(size_1);

baseAddr_0.resize(size_1);

for (int i = 0; i < size_1; i++) {

GridCell& baseAddr_1 = baseAddr_0[i];

read_GridCell(baseAddr_1);

}

}

Pos param_head;

read_Pos(param_head);

Move ret = get_move(param_grid, param_head);

write_Move(ret);

flushStreams();

}

}

}#include "game_types.h"

void init(GridCell& snake_id, uint32_t num_rows, uint32_t num_cols, uint32_t num_snakes);

Move get_move(std::vector<std::vector<GridCell>>& grid, Pos& head);Server-side Interaction

Now finally, we need the actual server code that is running the games to be able to smoothly interact with running agents. To do this, I leveraged the full power of rust's procedural macro system. With a single line of rust that looks like make_server!("res/games/nzoi_snake.game");, all the serialization logic is created and an Agent struct is defined that allows you to easily call the functions an agent has defined. The Agent struct also makes full use of asynchronous rust. All of this means, that if you want to get the next move for a snake all you have to do is something like:let res = agent.get_move(&grid, &head).await;Executing Untrusted Code

Executing untrusted code is at the core of this project. Students can submit any valid C++/Python program and it may be run. This typically poses a serious threat. However, there are already many pre-existing solutions.I used the IOI Isolate sandbox to solve this issue. The Isolate sandbox is maintained by Martin Mareš from the International Olympiad in Informatics' International Scientific Committee. It is used in the IOI and many other programming contests to run code students submit, so it seemed like the perfect option. It allows code to be run with very restricted permissions. Namely, the way I use it, when agents run they:

- Cannot spawn subprocesses

- Cannot access the internet, or the server's local network

- Cannot read or create any files

- Can only use a limited amount of memory

SQLite

I used SQLite3 as a database to ensure that any data persists between program restarts. The database is quite simple, it stores only "users" and "agents". While the schema was quite simple I did end up using an ORM (sea-orm) which perhaps ended up being a little bit overkill.Asynchronous Rust Code

The async engine I used was async-std. There wasn't much reason behind this, it just seemed like a reasonable choice. I did end up regretting this a little though. One of the main annoyances was that a lot of other async rust crates use tokio instead, which limited the number of creates I could use. Secondly, the facilities async-std has for reading/writing from files/pipes (for example, to communicate with agents) is rather limited. For example, the only method it seems to offer for reading is Read::poll_read(...) does not actually return a future, so I ended up having to build my own future types around them. For example, my implementation for reading ended up looking like below.impl<'data> Future for ReadFuture<'data> {

type Output = Result<(), Error>;

fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut std::task::Context<'_>) -> std::task::Poll<Self::Output> {

if self.remaining == 0 { // If future was constructed to read 0 bytes

return std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok(()));

}

let res = {

let ReadFuture {ref stdout, ref mut data, ref pos, ref remaining} = &mut *self;

let mut stdout = stdout.lock().unwrap();

let pinned = Pin::new(&mut *stdout);

pinned.poll_read(cx, &mut data[*pos..*pos + *remaining])

};

match res {

std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok(0)) => std::task::Poll::Ready(Err(Error::new(ErrorKind::UnexpectedEof, "Unexpected EOF"))),

std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok(bytes)) => {

self.pos += bytes;

self.remaining -= bytes;

if self.remaining == 0 {

std::task::Poll::Ready(Ok(()))

} else {

cx.waker().wake_by_ref();

std::task::Poll::Pending

}

},

std::task::Poll::Ready(Err(e)) => std::task::Poll::Ready(Err(e)),

std::task::Poll::Pending => std::task::Poll::Pending,

}

}

}HTTP/SSE

For this project, the HTTP server was built from scratch (on top of TCP/IP). While this is definitely not the most efficient way to do it (and probably not the safest way), it was quite educational. Surprisingly, it was not too difficulty yo implement, it was only about 850 lines of code quite a few of which are just big match statements over all the possible response codes.To allow users to see lives games, I originally used WebSockets. However, the way I had set it up, the websocket server would need to run separately on a different port to the HTTP server. This made it more difficult to set up port forwarding for the server, so I ended up just switching to Server-Sent Events (SSE), which ended up not being too difficult to implement on top of my HTTP setup. The only real difference is that you somehow need to keep the TCP connection alive for longer than you usually would.